Sequence to Sequence Modeling

Today, we look a historic model: the encoder-decoder architecture in sequence-to-sequence modeling (Sutskever et al., 2014). In this post, we will walk through the motivations behind this model, and probe further into the model architecture.

Motivation

Sequence-to-sequence modeling can be applied to any task involving sequences, such as speech recognition, question answering, and neural machine translation (NMT). Let’s start with the motivating example of translating the English sentence “I am walking” into German (which yields “Ich laufe”). To convert each input sentence to a form for neural networks to understand, we break down the sentence into tokens, where say word-level tokenization means the sequence “I am walking” is converted into three tokens ‘I’, ‘am’, and ‘walking’. The tokens are then converted into word embedding form, a many-dimensional continuous representational space where words with similar semantics are closer in distance to one another (Mikolov et al., 2013). Given that our input sequence contains three tokens, how do we feed it into the neural network to generate our desired output of two tokens?

Herein lies the problem with using a feedforward/recurrent network in NMT- the input and output dimensions of a network have to be fixed, whereas input and output sentences have varying lengths. A possible but highly impractical workaround involves training \(n \times m\) networks for all desired combinations of input size of \(n\) tokens and output size \(m\), where one can see that to translate sentences of \(\leq 10\) words we require an ensemble of \(100\) neural models!

Model

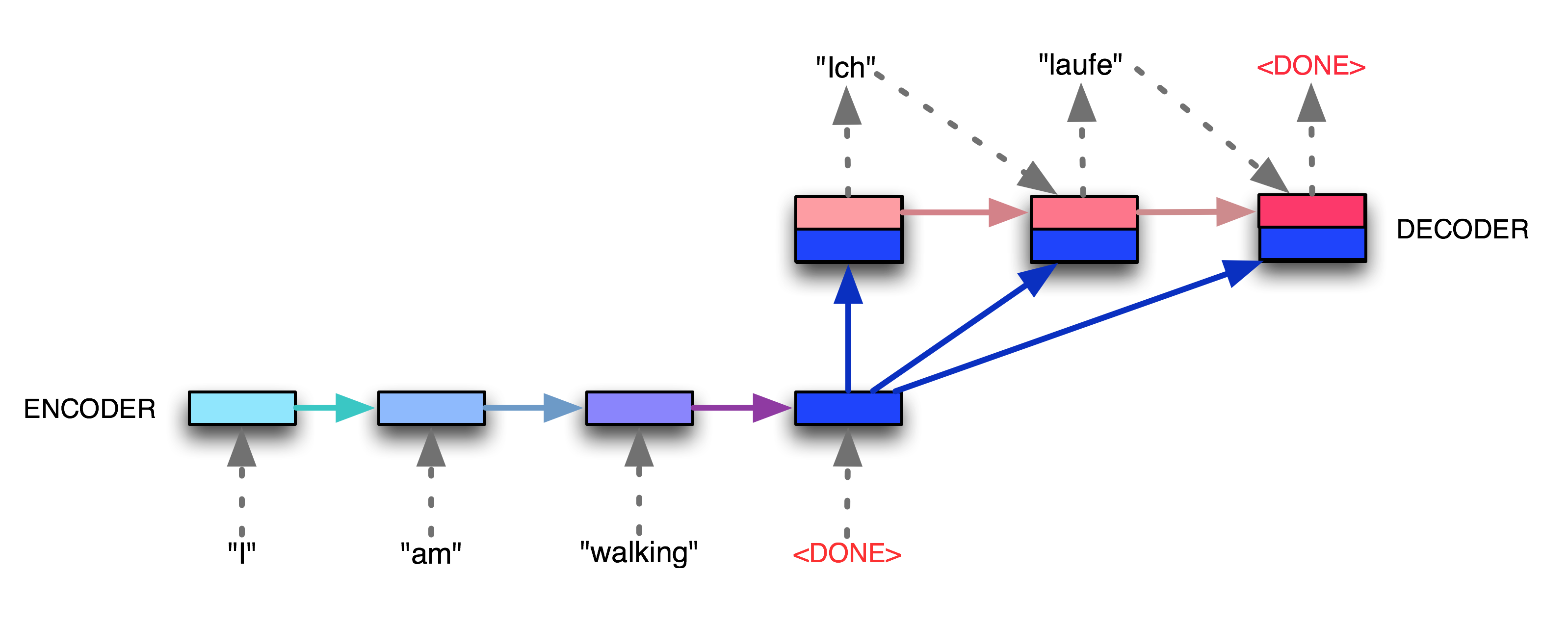

In the motivating example, we were thinking about how to fit sequences with varying lengths into the network. To bypass the spatial constraint of having a fixed input dimension in our network, we instead process it temporally- we first pass the input sequence token-by-token into an encoder network to generate an encoded vector of the input sentence, which is then fed into a decoder network to generate the translated network.

Source: Medium

Let’s return to our motivating example, illustrated above. The encoder reads the input sequence, updating its hidden state as input tokens are fed until it encounters the delimiting token ‘<DONE>’ (denoted by the blue color encoder turning darker). The final encoder state is then fed into the decoder network as input to generate the first translated output ‘Ich’. In each time-step, the decoder output token in the previous time-step is concatenated with the final encoder output and subsequently fed into the decoder to produce the next token. This is repeated until the decoder generates the ‘<DONE>’ token.

By reading the sequence in token level and using two separate networks for parsing and generation, we are able to bypass the fixed input/output dimension problem.

Musings

Intuitively, one might wonder if we can use just one network to encode and decode. One slight issue is the fact that for input and output token dimensions \(n\) and \(m\), the encoder and decoder input dimensions are \(n\) and \(n + m\) respectively. This can be bypassed by having an input dimension similar to that of the decoder, concatenating the input sequence tokens with an \(m\) dimension 0 vector. Update 19/12: A study on the transfer learning abilities of a text-to-text Transformer shows the theoretical benefits of the encoder-decoder architecture over an encoder-only (e.g. BERT) or decoder-only (e.g. language model) architecture (Raffel et al., 2019). Concretely, although the encoder-decoder model has twice as many parameters, the computational cost is \(\mathcal{0}(L)\) for \(L\) layers in both cases. This is because the \(L\) layers in a language model has to be applied to both the input and output sequences, whereas for the encoder-decoder model the \(L\) layers of the encoder and decoder acts on only the input and output sequences respectively.

The more consequential benefit in having two networks is in reducing the burden of having to learn to parse and generate in the same network. (HuggingFace, 2019) surmises that transfer learning would be much easier when having two networks, using a language model pre-trained on the source language as the encoder, and one pre-trained on the target language for the decoder. This would in theory be very useful for low-resource translation, where obtaining a sizeable corpus of the low-resource language is a challenge.

Comments