Binary Neural Networks

Binary Neural Networks (BNNs) are an extreme form of quantization in neural networks, where the weights are represented as binary digits taking on the values +1 or -1. While extremely space efficient (\(32 \times\) smaller than floating point values) and compute efficient (using XNOR operators to compute values), they are notoriously difficult to train and suffer from accuracy deprecation due to the extreme low-bit representation. In this post, we explore some key works in this field.

BinaryConnect: Training deep neural networks with binary weights during propagations (2015)

Courbariaux et al first introduced BNNs through a method BinaryConnect, which consists in training a deep neural network with binary weights during forward and backward propagations. Applying a DNN mainly consists in convolutions and matrix multiplications. The key arithmetic operation of DL is thus the multiply-accumulate operation.

BinaryConnect constraints the weights to either \(+1\) or \(−1\) during propagations, by binarizing real-valued weights either deterministically or stochatiscally. The deterministic method is trivial (\(+1\) if \(w_{b} \geq 0\), \(-1\) otherwise), whereas the stochastic method is as such:

\[w_{b}=\left\{\begin{array}{ll}{+1} & {\text { with probability } p=\sigma(w)} \\ {-1} & {\text { with probability } 1-p}\end{array}\right.\]where \(\sigma\) is the “hard sigmoid” function:

\[\sigma(x)=\operatorname{clip}\left(\frac{x+1}{2}, 0,1\right)=\max \left(0, \min \left(1, \frac{x+1}{2}\right)\right)\]As a result of the binarization, many multiply-accumulate operations are replaced by simple additions (and subtractions). This is a huge gain, as fixed-point adders are much less expensive both in terms of area and energy than fixed-point multiply-accumulators.

Binarizedneural networks: Training deep neural networks with weights and activations constrained to +1 or -1 (2016)

Courbariaux et al (2016) introduced a method to train BNNs at run-time, and when computing the parameters gradients at train-time, showing that it is possible to train BNNs on MNIST, CIFAR-10, and SVHN, achieving nearly state-of-the-art results. During the forward pass (both at runtime and train-time), BNNs drastically reduce memory consumption (size and number of accesses), and replace most arithmetic operations with bit-wise operations.

The famous XNOR kernel uses a method to speed up GPU implementations of BNNs, sometimes called SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) within a register (SWAR). SWAR concatenates groups of 32 binary variables into 32-bit registers, and thus obtain a 32-times speed-up on bitwise operations (e.g, XNOR). Using SWAR, it is possible to evaluate 32 connections with only three instructions: \(a_{1}+=\operatorname{popcount}\left(\operatorname{xnor}\left(a_{0}^{32 b}, w_{1}^{32 b}\right)\right),\) where \(a_{1}\) is the resulting weighted sum, and \(a_{0}^{32 b}\) and \(w_{1}^{32 b}\) are the concatenated inputs and weights. Those three instructions (accumulation, popcount, xnor) take \(1 + 4 + 1 = 6\) clock cycles on recent Nvidia GPUs, resulting in a theoretical Nvidia GPU speed-up of factor of \(32/6 \approx 5.3\).

Xnor-net: Imagenet classification using binary convolutional neural networks (2016)

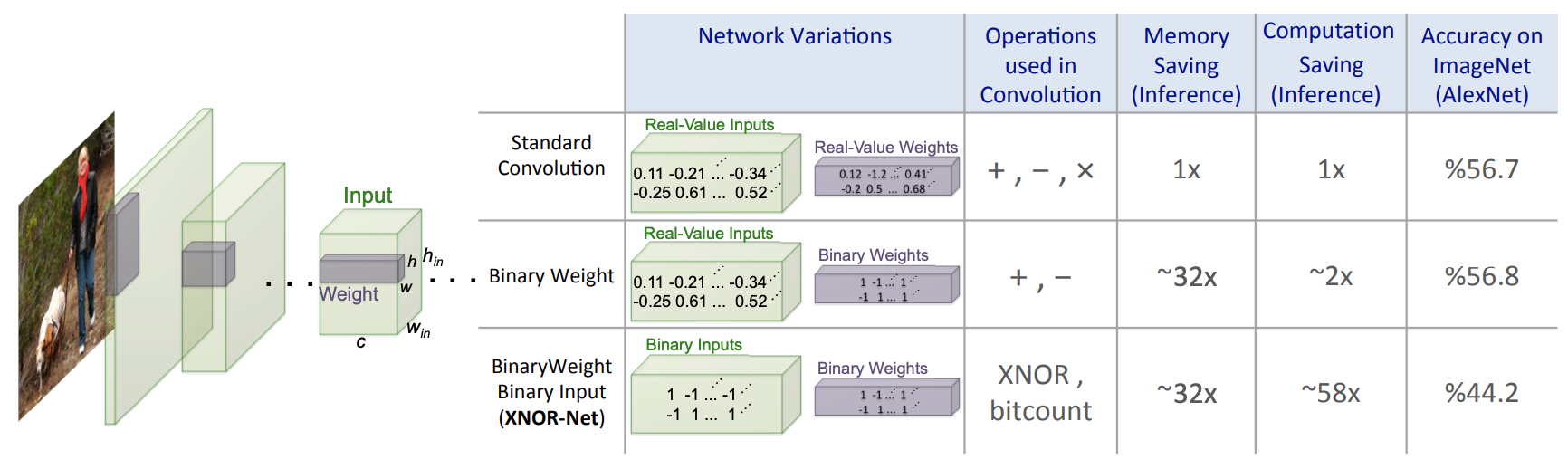

Rastegari et al proposed two variations of binarization in a CNN: 1) Binary-Weight-Networks, when the weight filters contains binary values, and 2) XNOR Networks, when both weigh and input have binary values.

As seen from the figure above, in Binary-Weight-Networks, all the weight values are approximated with binary values. Hence, CNNs with binary weights is significantly smaller (\(\approx 32 \times\)) than an equivalent network with single-precision weight values. In addition, when weight values are binary, convolutions can be estimated by only addition and subtraction (without multiplication), resulting in \(\approx 2 \times\) speed up. On the other hand, for XNOR-Networks where all of the operands of the convolutions are binary, the convolutions can be estimated by XNOR and bitcounting operations, resulting in accurate approximation of CNNs while offering (\(\approx 58 \times\)) speed up in CPUs (in terms of number of the high precision operations).

Contrasting the XNOR-Net with previous works, specifically the aforementioned BinaryConnect (utilizing Expectation Backpropogation), XNOR-Net works better on larger datasets (e.g. ImageNet). It also outperforms the follow-up BinaryNet by a large margin. This was illustrated in the top-1 classification accuracy of 56.8% by Binary Weight Networks, compared to 56.6% from the full precision AlexNet and 35.4% from BinaryConnect. For binary input compression, the proposed XNOR-Net scored 44.2% over BinaryNet’s 27.9% on the same test.

Training a binary weight object detector by knowledge transfer for autonomous driving (2018)

To ameliorate the accuracy deprecation when training BNNs, Xu et al proposed a knowledge transfer technique as a way to train the BNN using a pre-trained full-precision teacher network. The BNN is trained to mimic the responses of the intermediate layers of the teacher network, by minimizing difference between outputs of student and teacher networks. This achieves a compression ratio of 25 - 30 when compressing the DarkNet-Yolo and MobileNet-Yolo, while maintaining comparable mean average precision scores when tested on the KITTI object detection benchmark.

Back to simplicity: How to train accurate bnns from scratch? (2019)

This paper proposed a new BNN architecture BinaryDenseNet, maintaining rich information flow of the network through shortcut connections and increasing feature map dimensions. They have achieved \(18.6\%\) and \(7.6\%\) relative improvement over the state-of-the-art XNOR-Network and Bi-RealNet in terms of top-1 accuracy on ImageNet respectively.

Conclusion

In this post, we explore some key ideas surrounding binarizing neural network weights for time and space efficiency. This is a really interesting idea, although several key challenges remain to make them viable options for runnning on edge devices.

Comments